The Crime Decline, Mass Incarceration & Societal Well-Being

– Thomas Ulen

One of the most dramatic events in the United States of the past almost 30 years has been the remarkable decline in the amount of crime. Since 1991 there has been an almost (an important qualifier, as we shall see) continuous decline in both violent and nonviolent crime in the United States.

At the same time that this decline was occurring, there was an increase (although not a continuous increase, as we shall also see) in the number of people incarcerated in prisons and jails in the U.S. The figures are stark. In 1980 there were approximately 500,000 people being held in all federal and state prisons and local jails in the country. By 2005 there were 2.5 million people incarcerated in the United States. That figure was by far the highest rate of incarceration in the developed world. In addition, the United States accounted for 25 percent of all the prisoners in the world.

These two developments raise mixed emotions. The crime decline has been, as Professor Sharkey demonstrates, an unqualified social benefit. On the other hand, the fact that recently 1 in every 100 people was incarcerated raises mixed emotions. There are large direct and indirect costs of incarceration on that large scale. The direct costs of building, maintaining, and staffing prisons and jails are immense, estimated to be around $80 billion per year. The indirect costs to the individuals incarcerated and their families and communities in the lives that are disrupted and frequently never quite put back on track are also immense. If, however, that high rate of incarceration and its costs have played a significant role in causing the decline in crime, then just possibly the mass incarceration may have been worth pursuing. Even if that is so, it does not speak well for U.S. society that we had such high rates of crime before 1991 and had, apparently, to adopt such draconian measures to reduce those crime rates.

These matters have been the subject of a great deal of scholarly inquiry. That scholarship has focused on two related questions: First, why did crime decline so dramatically after 1991? And second, what role did “mass incarceration,” as it is called, play in the crime decline? The payoff to getting correct answers to these questions is extremely high. For instance, to the extent that we can identify the causes of the long decline in crime (and presumably, the causes of the large rise in crime in the late 1960s, 1970s, and 1980s), the greater our ability to adjust policy levers so as to stave off a future increase in crime (on the assumption that the factors we identify repeat their causal roles in the future) or to reduce crime if it spikes. Relatedly, if we can identify the reasons for increases and decreases in the rate of crime, the more focused our criminal justice policy can become. Although the scholarly search for reasons for fluctuations in the crime rate has become far more sophisticated, there are still a distressingly large number of potential reasons adduced to explain both the rise and fall of crime in the U.S. and, as a result, the lack of a clear, agreed-upon account of what happened and why after 1991. In view of that hodgepodge, our criminal justice system policy is struggling to figure out what lessons to take from the last 30 years.

As the readers of this journal will know, the field of law and economics has been deeply interested in criminal law and punishment issues for a long time. One of the foundational articles in the field is Gary Becker’s 1968 article on the economics of crime and punishment, which shifted the focus on crime away from socio-economic causes to the consideration of incentives to commit crime and to avoid punishment. Many readers will be familiar with this literature, including the remarkably robust literature over the last 40 years on the deterrent effect of the death penalty.

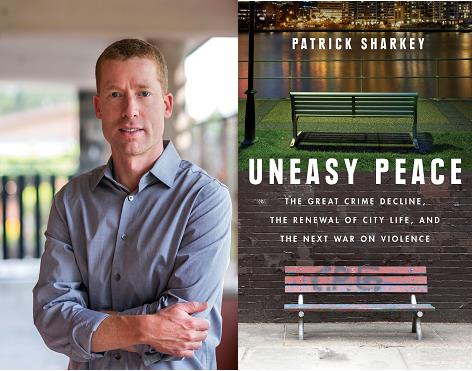

The books that I shall review here – John F. Pfaff, Locked In: The True Causes of Mass Incarceration and How to Achieve Real Reform (2017) and Patrick Sharkey, Uneasy Peace: The Great Crime Decline, the Renewal of City Life, and the Next War on Violence (2018) – examine two different aspects of crime in the United States. Pfaff focuses on mass incarceration and offers a novel theory of the reasons for mass incarceration and empirical evidence to support that theory. Sharkey focuses on crime and the urban landscape. In particular, he examines the great benefits of the crime decline to urban living and particularly to urban minority communities.

Before turning to those works, I shall, in Section II, give some background on what is called the “great crime decline” of the 1990s and early 2000s.

Then in Section III I shall turn to a discussion of Professor Pfaff’s account of why there has been such heavy use of incarceration as a crime-deterring strategy in the United States. He argues that society has been driven to overuse imprisonment because prosecutors have overly strong incentives to pursue imprisonment for criminal offenders. Pfaff suggests that the result is that, from a societal well-being perspective, there are too many prisoners. He offers correctives that will, he argues, trim prosecutors’ incentives to overuse imprisonment.

Then in Section IV I turn to a discussion of Professor Sharkey’s account of the important relationship between the level of crime and societal well-being. He first shows that the increase in crime in the 1960s through the late 1980s had a wide-ranging adverse effect on society. Crime obviously has very ill effects on the victims of crime, but Sharkey points out that the knock-on effects of crime on all of society are also devastating. It follows, as he demonstrates, that when crime declines, the benefits to society as a whole are very large. In the course of these important demonstrations, Sharkey identifies at least one interesting and heretofore underreported causal effect on the crime decline.

A brief conclusion follows.

A fair question is, “What has all this got to do with India?” The matters discussed in these two books should have appeal to those who are curious about broad social trends in crime, why crime rates fluctuate, what the consequences for societal well-being are when crime declines or increases, and what tools the United States has used to combat crime increases and whether those tools are effective. Moreover, those who are interested in the field of law and economics ought to find these books of interest in that they explore areas in which law-and-economics scholars have taken a deep interest.

Read the full article here.

This is actually helpful, thanks.